Insulin On Board

Many people have asked me questions about our insulin pumps, and I thought it might be worthy of a post. Things like: Is that the bionic pancreas I've heard all about? So that thing takes care of it all, and they can eat whatever they want? Does it automatically dose insulin? So basically, they have that and you don't have to really do anything? I think we've probably heard it all. And I'm always happy to answer questions. Because if you're asking questions it means you're interested to learn more about Type 1, and that makes me really happy.

When a person is Type 1 they need insulin to stay alive. Period. End of story. There are many different ways to administer said insulin, and no one way is better or worse than another. Depending on your lifestyle, what you're daily routine entails, and access to healthcare and insurance, all these things (plus numerous other factors!) may dictate how you receive your lifesaving medicine. There are 3 different ways to inject insulin: syringe, pen, and pump. There is an inhalable version they've been testing and pushing to market recently but I don't know anyone who uses this, and I'm not familiar with its reliability and what not. Currently needles are a necessary evil for anyone with Type 1, one which there's really no way around.

Essentially there are 2 kinds of insulin that are commonly used in the US: fast-acting and long-acting. Fast-acting is the insulin that is used for mealtimes and corrections of high BGs. Long-acting insulin, however, is injected once a day and works on the body over a long amount of time, typically 24 hours. This long-acting insulin is what keeps the organs of the body functioning and helps maintain a steady blood sugar when you remove things like food, exercise, stress, etc from the equation. Our bodies require a baseline level of energy for things like breathing, pumping blood, blinking eyes, and a long-acting insulin is necessary for the synthesis of this energy demand.

The syringe and insulin pen are quite similar. In both cases you need to manually inject yourself with insulin every time you eat something that requires a bolus, any time you need to lower a high blood sugar, as well as once a day for your dose of long acting insulin. The syringe is, well, a syringe. The pen is also a syringe, but the main difference is that there is a cartridge of insulin that stays attached, much like one might think of a cartridge of ink in a pen. You turn the dial on the pen to the amount of insulin you need to inject and the pen draws up the correct bolus. We used a pen with Ollie soon after his diagnosis, before he started his pump. It's a convenient alternative to the barebones syringe, and minimizes the chance of over/under dosing for injections.

Insulin pump therapy is quite different from the MDI (Multiple Daily Injections) of pens and syringes in many ways, but the biggest difference is the way the insulin is administered and the kind used. With an insulin pump there is no need to take a long-acting insulin. An insulin pump is continually attached to the T1D, and is continually dripping insulin into their body. Instead of the background insulin of a long-acting, the pump slowly drips a small amount of insulin to deal with the things like breathing, heart function, etc. Think of it as a leaky faucet. The pump is a computer that is programmed with the patient's specific insulin needs. There can be different amounts of insulin that drip at different times during the day (like while you're sleeping versus a time when you're typically more active). You can't do this as easily with a long-acting insulin since you only take it once a day and cannot adjust how the body responds to the domino reaction that takes place once it enters your system. There's a downside to the pump mimicking the slow release of the long-acting insulin: if the pump fails in any way, or if the pump is disconnected from the body, the wearer will not receive any insulin and this can be potentially life-threatening.

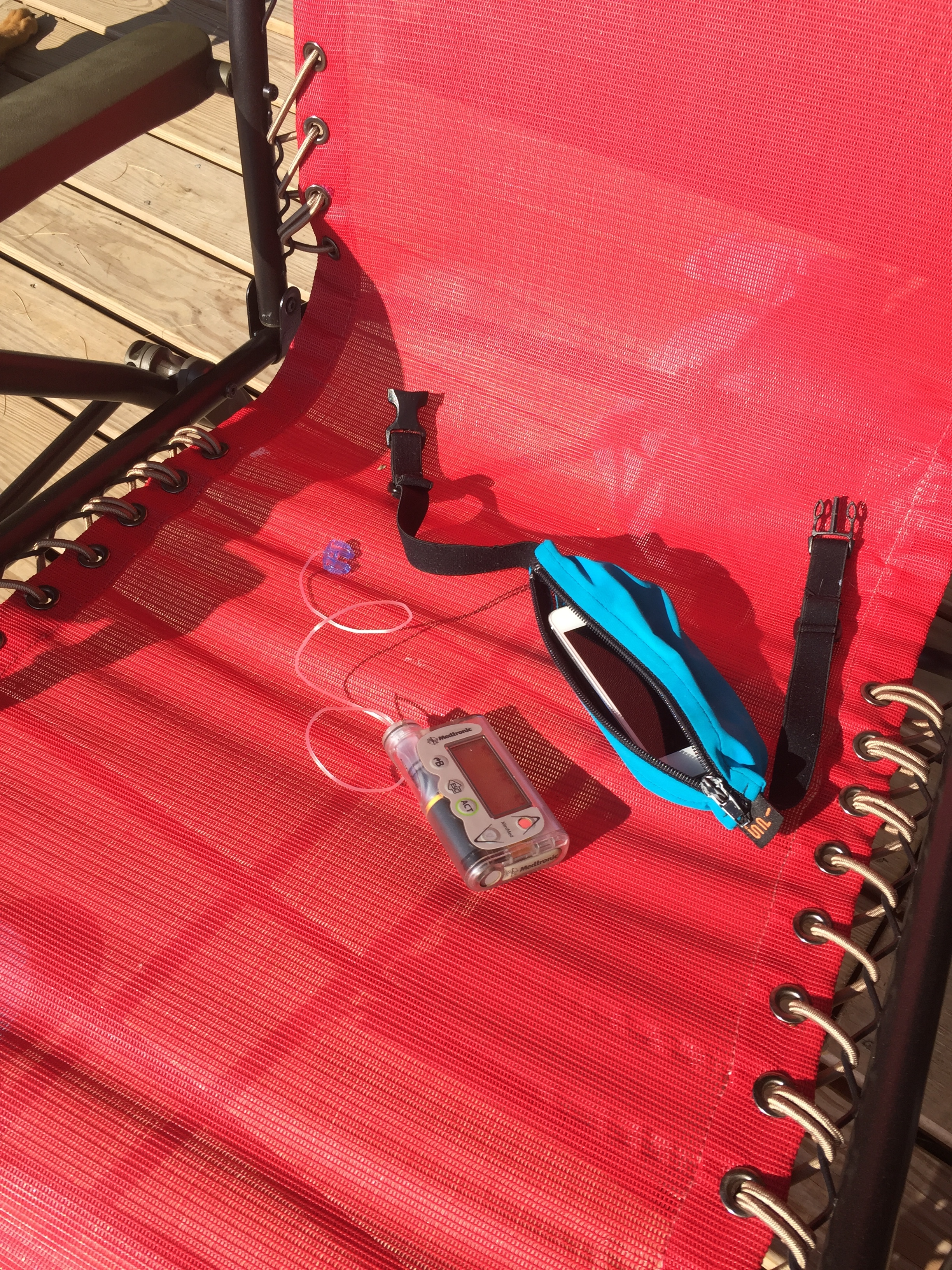

There are many different styles of pumps, and again you choose the pump that best fits your needs. Some pumps are attached to the body with tubing connected to another small device which houses the insulin cartridge and computer (this is what our family uses), while others are a tubeless system where the insulin cartridge is attached directly to the body and the computer is carried separately. Regardless of the style, they all basically work the same way; they all have a basal drip of insulin (functioning like a long-acting insulin), and the ability to bolus fast-acting insulin for mealtimes and blood sugar corrections. The pump also keeps track of how much insulin is currently active (most fast-acting insulin remains active in the system for 3 hours, peaking at 1.5 hours) as well as the various carb to insulin ratios everyone requires. We enter the amount of carb for each meal, as well as their blood sugar, and the pump does all the math (keeping track as well to how much insulin is still active in the body from a prior bolus) and suggests a bolus amount to get them to their ideal blood sugar. It's pretty incredible. Another benefit we see to using a pump is the freedom. Any time you might need a little bit of insulin you simply punch it into the pump and it's done. If Ollie decides he wants a second (or third or fourth) helping of dinner, we simply enter it into the pump. If he were on MDI he would need to make the choice of taking another shot or two, or passing on eating. When you're growing as quickly as Ollie is, and needing to eat and snack as much as he does, this is a huge plus! We find using the pump much more conducive to maintaining more stable blood sugars.

Marshall's pump, however, takes it to a new level. His pump is the newest version and works in concert with his CGM. The CGM alerts the pump when his blood sugar is rising or falling and the pump adjusts the drip of insulin accordingly to bring him back to his "normal" range. It's not a 100% closed loop, as he still needs to take a role in bolusing for meals, and correcting low blood sugars with external sugar (candy bars or juice for example). The pump will slow down or even suspend insulin delivery if blood sugars drop low, but it's not failsafe by any means. It does mean that, since starting this pump nearly a year ago, Marshall has maintained the best blood sugars of his life as a T1D. It isn't a cure by any means, it just makes the day to day a little easier. The only reason the kids don't have a similar version of the pump is because the CGM needed to communicate with the pump is unable to communicate with me, Marshall, and the school nurses. This means that if the kids start to go low or high, the adults are unable to intervene with sugar or insulin. With the CGMs they are currently using we are able to follow along with their CGM data, aware when they are going high or low. No matter how great this closed loop is, and no matter how great the data is on "extended blood sugar control", it only takes one untreated low blood sugar to become very very serious. That's not a risk Marshall and I are willing to take on the kids.

So this means that Marshall and the kids need to wear their pumps all the time whether they're sleeping, or riding their bikes, or sitting in class or at work. The ONLY times they disconnect their pumps are when they shower or go swimming because their pumps are not waterproof. This proves tricky when you've got two waterbug kids who would stay in the lake all day if they could. But they can't, because they're not getting their "leaky faucet" drip of insulin to cover the baseline insulin needs of their body. Regardless of the fact that they're burning off sugars while they dive and swim around, their body still needs insulin to stay alive. So they remove their pumps when they get in the water, and have to come out and "plug back in" every hour or so and get a small amount of insulin before they can disconnect and cannonball back in the water. The longest they can be "unplugged" is about 90 minutes. After that amount of time the body will begin to produce ketones when it starts using fat stores for energy, and as I've discussed before, the only way to clear ketones is with insulin. Hence, the need to be connected to their pumps 24/7. For someone like Ollie, who is constantly moving and has the metabolism of a hummingbird, it also means that he has to be eating snacks while he comes out for breaks, otherwise his blood sugar will drop (which sometimes still happens).

The pump is attached to the body with a sticky patch and a cannula, in a way similar to an IV. The cannula is inserted subcutaneously, just as a syringe would be inserted, via a hollow needle and remains under the skin in order to deliver the insulin from the pump. The cannula is very small, only a few millimeters long, and is made of a flexible plastic These pump sites need to be inserted on a fatty area of the body, and not into muscle. Ollie and Walker are very lean so this means the only place we can currently use are their, as we affectionately refer to them, "squishy bum cheeks". Pump sites need to be changed every 3 days and rotated around the body to ensure the tissue can receive the insulin as it should. After 3 days insulin also starts to become less effective since it has been worn so close to the body and the temperature is elevated; typically insulin should be kept cool. So every few days we go through this process of their site change. Sometimes it hurts a lot, while other times they barely feel a thing. But one shot every three days, rather than the 7 or 8 per day of syringes, certainly makes it worth while.

We are extremely fortunate to have access to such incredible, life-saving technology. There are so many Type 1s in the world, and even in our country, who don't have the luxury of choice. We have to choose our insurance plan wisely, and yet many days I still spend hours on the phone fighting for the necessary supplies for my family. Access to affordable health care is, literally, a life and death issue for my family. Many argue that a Type 1 can maintain their health with lower cost means like syringes and NPH insulin (if you're interested in what this is, I'm happy to discuss). My response to them is that quality of life plays a vital role in long term health for T1Ds. My kids and husband will have diabetes for the rest of their life, or until we find a cure. This taxes their emotional well-being and anything we can do to lessen the burden supports their health, both physical and emotional. Sure, this exceptional care comes at a high price, but it's one that is necessary for their survival.

If you have any questions about pumps, or syringes, or even insurance plans and health care, feel free to comment at the bottom of this post or email me directly.